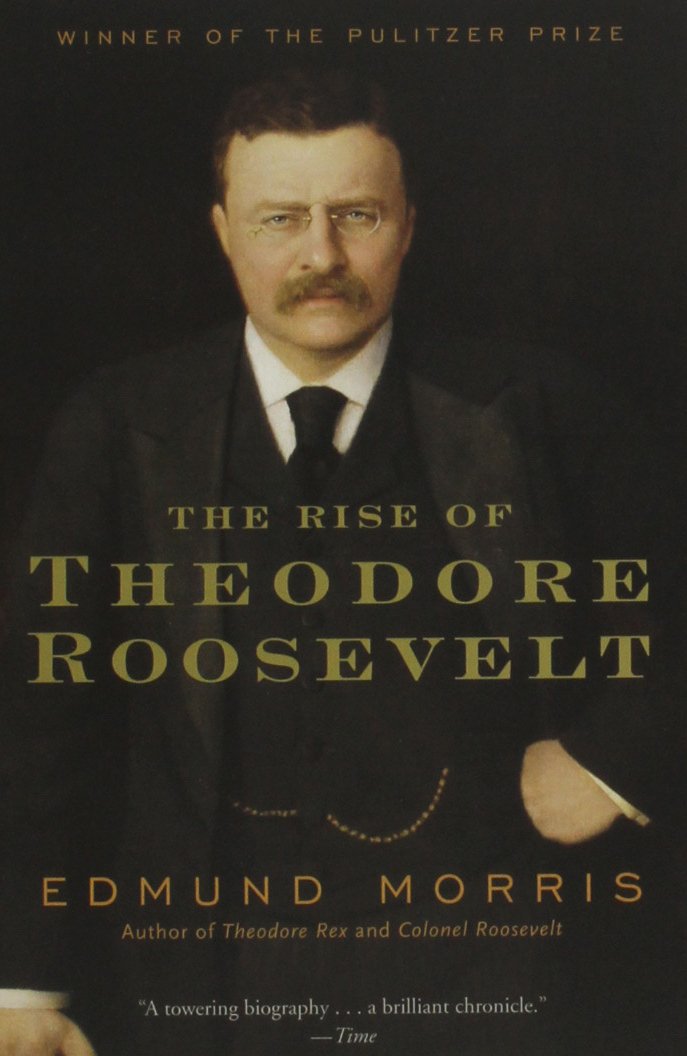

I recently decided to take a look at the life of one of the greatest men to ever live, Theodore Roosevelt. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt by Edmund Morris describes Roosevelt’s life up to the moment when he became President of the United State. In it Morris recounts many of the stories that have become famous about Roosevelt’s early life; one of which was how as a boy he was asthmatic, frail and often sick. Recognizing the importance of a strong, healthy body, his father called Theodore in to tell him that he must make his body, as told by Morris:

“Theodore,” the big man said, eschewing boyish nicknames, “you have the mind but you have not the body, and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body. It is hard drudgery to make one’s body, but I know you will do it.”

Mittie, who was an eyewitness, reported that the boy’s reaction was the half-grin, half-snarl which later became world-famous. Jerking his head back, he replied through clenched teeth: “I’ll make my body.”

At a young age Roosevelt was already showing that he had a powerful mind, despite his sickly body, expressing interest in a variety of subjects and frequently reading books. After talking with his father he began working out regularly to build his body and after a few years was no longer the frail, sickly boy he had been and was already suffering from asthma attacks less frequently.

Years later upon returning to New York after having spent a few months working at his ranch in the Dakotas, many were surprised to see him fitter than ever. Morris describes what a friend who had not seen Roosevelt in years had to say after seeing him again:

Throughout that summer Roosevelt continued to swell with muscle, health, and vigor. William Roscoe Thayer, who had not seen him for several years, was astonished “to find him with the neck of a Titan and with broad shoulders and stalwart chest.” Thayer prophesied that this magnificent specimen of manhood would have to spend the rest of his life struggling to reconcile the conflicting demands of a powerful mind and an equally powerful body.

Morris also notes that after his time spent ranching in the Dakotas there are no further mentions of asthma in his correspondence, he had finally built a body to be worthy of the powerful mind it also contained.

Both a powerful mind and body take time and dedication to develop and can find themselves at odds as one must balance the time required to maintain both. The work required to build and maintain a healthy body can also help one to build a powerful mind, as the discipline that must be exercised to workout consistently can also be used to help motivate oneself to read and study frequently as well.

Looking back at some other historical figure’s thoughts I found that a similar recognition of the importance of building both a strong mind and body was expressed by Henry David Thoreau in Walden. Using the idea of our body as a temple, Thoreau explains how it is our responsibility as the painters and sculptors of our bodies to shape them into our own unique temple, saying:

Every man is the builder of a temple, called his body, to the god he worships, after a style purely his own, nor can he get off by hammering marble instead. We are all sculptors and painters, and our material is our own flesh and blood and bones. Any nobleness begins at once to refine a man’s features, any meanness or sensuality to imbrute them.

If we practice restraint and consistently work at sculpting ourselves, over time we will eventually refine our body’s features, while if we frequently indulge ourselves, we will tend to, over time, mask them. Although it can’t be seen directly, we must also sculpt our mind, working to shape and build our knowledge of various subjects and life in general. Even though our mind cannot be seen visually, others can still can get an idea of it through their interactions with us, and learn whether we have been working to refine our mind as much as our body, or allowing it to atrophy.

Recognizing the difficulty and mental strenuousness of truly reading and studying a book beyond a superficial level, Thoreau makes an apt comparison to physical exercise, explaining:

To read well, that is, to read true books in a true spirit, is a noble exercise, and one that will task the reader more than any exercise which the customs of the day esteem. It requires a training such as the athletes underwent, the steady intention almost of the whole life to this object. Books must be read as deliberately and reservedly as they were written.

To read a book with deliberation and intention will tax ones mental abilities through the process of working to understand what an author is saying, and to more than just understand it; but to really absorb the ideas being expressed in a book and meld them into your own existing ideas. This process is one which requires a considerable mental effort that can leave one feeling exhausted and in need of a break or rest similarly to how a difficult workout will require a rest period before moving on to the next exercise.

The writing process takes a considerable amount of deliberation,consideration and thought on the part of the author to craft each line and express each idea clearly and concisely, yet we can frequently read these same sentences without stopping to give a second thought to what we just read. By reading with intention and putting in the mental work to truly understand what is being said we can help to justify the author’s efforts.

Without a strong body, the mind cannot grow to its full potential, as exercising the body can have positive effects on the brain. While, without a strong mind the body also cannot reach its full potential, as techniques which could be used to grow stronger or run faster may be missed. The body and mind work synergystically, improving one can help lead to even greater gains in the other.